March Issue

-

Vol 23|No 4|March 2014

Order McKenzie books online with a credit card

Bring Jamie to your school or district for a great workshop.

|

What have we done?by Jamie McKenzie (about author) |

Looking Back

The Internet came to schools with much fanfare in 1994-95, as browsers converted the previously text-based World Wide Web into something far more user-friendly and attractive. Some of us felt these information technologies might transform schools in dramatic ways as students would have wide open access to information much richer than what was available previously. We hoped the Internet would foster independent thinking and originality.

Pumped with high expectations, I wrote "Grazing the Net" in 1994 — which was republished in Kappan in 1998 and gained lots of attention. The main thrust of the article was the beauty of students being able to make up their own minds free of the normal constraints of textbooks, books, newspapers, news shows and conventional wisdom.

1994 - This article will show how schools may take advantage of these electronic networks to raise a generation of free range students — young people capable of navigating through a complex, often disorganized information landscape while making up their own minds about the important issues of their lives and their times.

Click here for a video overview of the original article.

Two decades later, how many of these possibilities came true?

Did we, indeed, raise a generation of free range students? Back then I warned that impressive learning results would only occur if schools clarified learning goals.

1994 - Will we see dramatic increases in student achievement to justify this investment? In many cases — those districts that fail to clarify learning goals and fund professional development — the answer will be "No!" There is no credible evidence that networks improve student reading, math or thinking skills unless they are in service of carefully crafted learning programs that show students how to interpret information and make up their own minds. |

First the Good News

During this past decade, two national organizations created assessment instruments to address the questions listed above. While intended to test the media literacy skills of college students, they have been adapted for use with high school students. ETS (Educational Testing Service) created the iSkills Assessment, and CAE (The Council for Aid to Education) created the CWRA (The College and Workplace Readiness Test). Both of these tests measure whether students can manage the complex information landscape to solve problems and make decisions.

Unfortunately, relatively few schools and colleges have been making use of such measures until recently, and the majority of American college students show a disappointing level of skill when it comes to wrestling with information challenges. While some have applauded the savvy of the so-called "digital natives" it turns out that familiarity does not by itself breed capacity.

Then the Bad News

The senior researcher who guided the assessment project at ETS, Irvin R. Katz, summed up his findings in dark terms:

Owing to the 2005 and 2006 testing of more than ten thousand students, there is now evidence consistent with anecdotal reports of students’ difficulty with ICT literacy despite their technical prowess. The results reflect poor ICT literacy performance not only by students within one institution, but across the participating sixty-three high schools, community colleges, and four-year colleges and universities. The iSkills assessment answers the call of the 2001 International ICT Literacy Panel and should inform ICT literacy instruction to strengthen these critical twenty-first-century skills for college students and all members of society.

Sadly, there has been very little credible measurement of skill levels. The terms information and media literacy are often used interchangeably and rather loosely. While there are quite a few projects that set the goal of enhancing literacy, most of these have failed to assess their progress with any instruments that will pass tests of reliability and validity.

The report from Irvin R. Katz "Testing Information Literacy in Digital Environments: ETS’s iSkills Assessment" (a PDF file) provides the most illuminating data I could find regarding current levels of literacy. It should be noted that we are talking about information literacy, not technology skill. As Katz points out in his introduction:

Technology is the portal through which we interact with information, but there is growing belief that people’s ability to handle information—to solve problems and think critically about information—tells us more about their future success than does their knowledge of specific hardware or software. These skills—known as information and communications technology (ICT) literacy — comprise a twenty-first-century form of literacy in which researching and communicating information via digital environments are as important as reading and writing were in earlier centuries (Partnership for 21st Century Skills 2003).

In 2003, ETS helped to form the National Higher Education ICT Literacy Initiative - a consortium of universities and colleges willing to help develop an assessment process to determine levels of literacy. Katz reports that they adopted the following definition of ICT literacy:

ICT literacy is the ability to appropriately use digital technology, communication tools, and/or networks to solve information problems in order to function in an information society. This includes having the ability to use technology as a tool to research, organize, and communicate information and having a fundamental understanding of the ethical/legal issues surrounding accessing and using information (Katz et al. 2004, 7).

The group then identified seven performance areas that are outlined in Katz's article. ETS then set about developing the iSkills Assessment.

ETS’s iSkills assessment is an Internetdelivered assessment that measures students’ abilities to research, organize, and communicate information using technology. The assessment focuses on the cognitive problem-solving and critical-thinking skills associated with using technology to handle information. As such, scoring algorithms target cognitive decision-making rather than technical competencies.

As mentioned earlier, Katz's article reports that early use of the iSkills Assessment showed that participating students had disappointing levels of literacy. The CWRA (The College and Workplace Readiness Test) would also prove illuminating, but public data showing student performance is quite limited except in those cases where a school may wish to use the data as a marketing strategy.

How did we go astray?

While Katz provides no data to help explain the disappointing levels of media and information literacy discovered during his use of the iSkills Assessment, he repeatedly contrasts literacy with technical prowess. For several decades schools have spent a fortune on equipment and networking without investing in literacy-focussed professional development and without clarity about learning goals. While some groups have established standards that mention literacy, none of these backed up their standards with assessment instruments with the validity of either the iSkills Assessment or the CWRA.

ISTE's NETS for Students 2007, for example, makes some laudable goal statements about 1. Creativity and Innovation, 2. Communication and Collaboration, 3. Research and Information Fluency, 4. Research and Information Fluency as well as Critical Thinking, Problem Solving, and Decision Making, but the organization offers no assessment model to give such goal statements teeth. Ironically, ISTE identified assessment as one of the "necessary conditions to effectively leverage technology for learning."

Assessment and Evaluation

Continuous assessment of teaching, learning, and

leadership, and evaluation of the use of ICT and digital

resources

And there we have it, sadly. We have seen too little investment in assessment and evaluation. And we have seen a foolish belief that the ownership of equipment will transform schools and learning in good ways. The data indicates that growth of information and media literacy is unlikely to occur without intensive professional development that focuses on those goals accompanied by assessment tied to those goals. For decades we have known that "the testing tail wags the program dog."

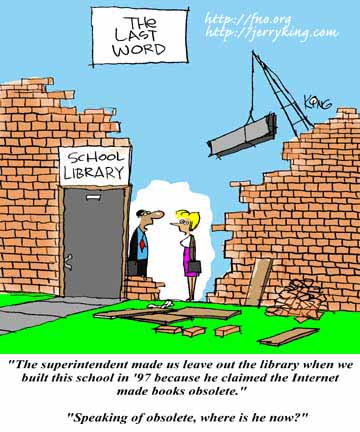

Dismantling Library Media Programs and Staff

It is notable that many school districts in the USA and Canada made severe library staffing cuts during the past two decades.

The ALA reported in 2010 that "the number of full-time certified school librarians has decreased significantly in 24 states."

In 2011 the Huffington Post reported "Librarian Positions Cut In Schools Across The Country" — providing numerous examples and data.

Many educational leaders argued that laptops combined with the Internet pretty much made libraries obsolete, even though teacher librarians were the ones trained to equip students with ICT skills. When the Gates Foundation funded a small schools project, libraries and librarians were left out. In many states such as Oregon and California, certified librarians were virtually eliminated at the elementary level and many high schools were forced to survive with thin staffing.

|

Even though some argued that teacher librarians were more important than ever — "Why We Still Need Libraries and Librarians" — staff reductions were commonplace and ongoing across the continent. It stands to reason that such staffing decisions would impede efforts to focus on ICT. Much of the program implementation in many school districts made technology paramount while neglecting information and media literacy. This focus on technology skills has proven foolish. |

When Goals and Assessment Match Up

In addition to the two tests mentioned above, a school might employ surveys like those below to determine to what extent teachers and students are devoting their time to acquiring information and media literacy. By matching program goals and assessment instruments, we have a basis for steering the program. Without such data, we are basically sailing blindly through fog. Ignorance is rarely bliss.

1. The Educational Daily Practice Survey (EDP).

The student version of the EDP assesses the frequency and the types of learning activities students are asked to perform. The teacher version assesses the frequency and the types of learning activities teachers assign. We would hope, of course, to see convergence of the two.

Using the EDP, schools can measure the effectiveness of programs by tracking evidence of change in the daily practice of participating teachers.

Desired Behavior |

. |

Daily appropriate use |

As teachers gain in skill, confidence and inclination, they and their students will begin reporting daily use of new technologies side by side with more traditional technologies such as books, Post-It Notes and Magic Markers. |

Continued self sustained growth |

Participating teachers report sustained acquisition of new technology skills along with an expansion of lesson design capabilities. |

Access for all students |

Without exception, students in classes of participating teachers report sufficient access to tools to manage assignments effectively. |

Self sustaining community of learners |

Participating teachers indicate that adult learning is collaborative, ongoing and informal. |

Technology invisible, transparent, natural |

Artificial, silly uses of new technologies subside and technology for the sake of technology is no longer evident. Uses of new technologies are comfortable, casual and unexceptional. |

Expanding definitions |

Classroom strategies and activities move from an emphasis on technologies and technology skills to focus on information literacy, research, questioning and standards-based learning. Students are challenged to analyze, infer, interpret and synthesize with a mixture of classical and digital tools. |

Support for engaged learning |

Students report that they spend an increasing percentage of their time on Engaged Learning tasks - taking responsibility for their learning in a collaborative, strategic and energized mode. |

Teacher as facilitator |

Both teachers and students report that teachers devote an increasing proportion of their class time to facilitating and guiding the learning of students as opposed to more |

Discerning use |

Participating teachers gain enough in confidence and discernment to identify technology uses and activities they have discarded or found unsatisfactory. They report movement toward quality and worth. |

Standards-based activities |

The technology activities are focused on improving student performance on demanding curriculum state standards. |

| © 2002, J. McKenzie, all rights reserved. |

Both versions of the EDP are available for free use by any school hoping to assess the impact of a technology program - whether the strategy involves laptops for all students, mobile laptop carts, classroom desktop units or lab-based programs.

- View Student EDP

- View Teacher EDP

- Download MS Word Version of Student EDP

- Download MS Word Version of Teacher EDP